Our world is marked by the convergence of complex challenges that impact food and nutrition security: pandemics, conflicts, climate extremes, and economic shocks affect millions globally. Boundaries between humanitarian and development responses are dissolving in fragile countries and driving global actors to promote the Humanitarian-Development-Peace Nexus (HDPN) as a unifying framework.

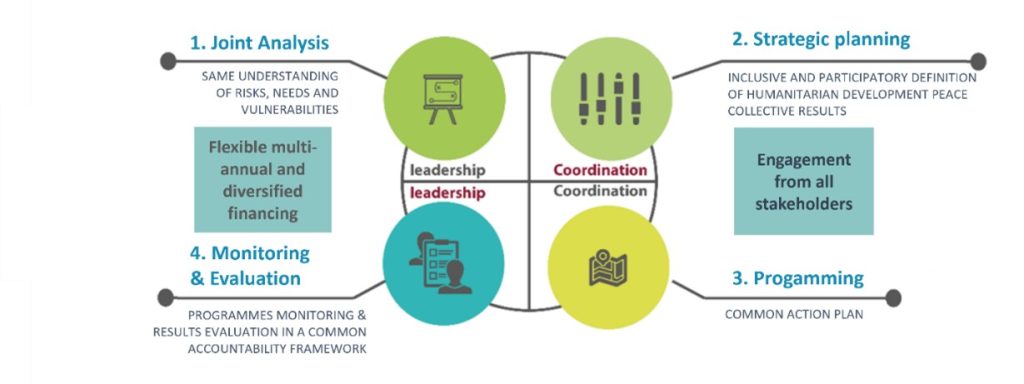

The HDPN framework includes a call to action for “strong cooperation, collaboration and coordination between humanitarian, development and peace building efforts in country”. Core principle of HDPN are convergence, resilience and integration for sustained impact. It champions a cohesive approach built on shared analysis, planning, action and M&E (Figure 1). This requires a cohesive data ecosystem that can inform short-and long-term responses.

Figure 1 HDPN Collaborative Framework (Source: adapted by NIPN from the United Nations Secretariat for Humanitarian Development Collaboration steering committee, November 2019)

What does it look like to apply a HDPN lens to Nutrition Information System (NIS)? Do humanitarian and development actors engaged with nutrition share common data priorities? Can these be addressed through a more unified data value chain?

DataDENT has been engaging with colleagues from European Commission- Joint Research Centre (EC-JRC), UNICEF, and National Information Platforms for Nutrition (NIPN) to explore these questions. Our first task is to identify how each community conceptualizes NIS and where HDPN principles might apply.

Defining NIS across humanitarian and development sectors

Humanitarian actors have a fairly unified understanding of the purpose and importance of a NIS. Historically, emergency actors collect and consolidate data on a focused set of outcomes including anthropometry in children and pregnant women, food security, and other factors related to crisis conditions. When monitoring interventions, humanitarian actors prioritize screening and treatment outcomes for malnourished children, as well as water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) interventions and the distribution of food and/or cash to vulnerable groups. Given their action-driven nature and shorter funding cycles (e.g. 6-12 months), humanitarian actors need high-frequency, high-granularity data to inform time-sensitive decisions about resource allocation and implementation. This data is often collected in “hot spot” areas through surveys and surveillance systems supported by international humanitarian agencies. Data sharing among agencies often occurs during stakeholder coordination meetings in the form of slides or spreadsheet files rather than a central database. At global level, there have been concerted efforts by the Global Nutrition Cluster and other humanitarian actors to define common emergency NIS indicators, data tools, and processes. One notable example is the Integrated Food Security Phase Classification (IPC), an analytical framework that classifies the severity and magnitude of both food insecurity and malnutrition. It is carried out annually or biannually in over 30 countries, offering a standardized approach to assessing food security and malnutrition, and using data to guide response. In South Sudan and Madagascar UNICEF, WFP and the GNC are working together to map and access data on the drivers of acute malnutrition for use in early warning and alert systems that drive responses in between annual IPC situation analyses.

If you ask development actors within and across countries to explain a NIS, you will get a much wider range of responses. Some will describe a dashboard or scorecard that consolidates data from multiple sources in a single interface. Others will talk about the inclusion of nutrition indicators in the Health Management Information System (HMIS) / District Health Information Software (DHIS-2). Several countries have developed unique multi-sector routine NIS that continuously collect food and nutrition indicators from each sector. The varied perceptions of what constitutes a NIS among development actors reflects the range of food and nutrition problems, the multitude of interventions and actions, and the diversity of actors involved in national multi-sector nutrition strategies. Compared to humanitarian contexts, development-oriented policy and program cycles are longer (3-5+ years). There is more emphasis on using NIS data to inform mid-to-long-term planning including monitoring trends across the entire population in nutrition outcomes prioritized by World Health Assemble (WHA)/Sustainable development Goals (SDG) targets and in scale-up and coverage of nutrition interventions. Currently, there is no consolidated guidance on which indicators countries should include in a multisectoral NIS; WHO-UNICEF TEAM has started to work on prioritized indicator lists to complement broader national NIS guidance and forthcoming guidance on nutrition indicators in HMIS. In addition to DataDENT’s work there are other multi-country efforts to strengthen NIS components. Since 2015, the NIPN project has worked across nine countries to strengthen analysis of existing data for nutrition decision making. Several other initiatives including EC-NIS project and Alive & Thrive have aimed to increase routine collection of nutrition data across multiple countries.

Bringing the HDPN lens to NIS

A core principle of NIS is that they should be ‘fit to purpose.’ There are unique factors driving humanitarian and development food and nutrition responses that make it unlikely that a fully unified NIS can be designed to meet all stakeholder needs. However, there are opportunities to bridge the divide and apply HDPN principles to strengthening national food & nutrition data value chains including:

- Align indicator sets. Engage both humanitarian and development actors in country in indicator prioritization exercises to see how they can be aligned. This is particularly relevant for food security indicators as there is a wide variety of potential indicators; alignment on 1 or 2 metrics will facilitate data sharing and comparisons across time and context.

- Advocate for common data gaps. Both humanitarian and development actors in Low Income Country (LIC) tend to overlook the need for data on diet-related non-communicable diseases (NCDs) including obesity, hypertension and diabetes; joint advocacy for an aligned set of indicators will increase the likelihood that countries will prioritize their collection.

- Share analytical innovations. The humanitarian community has been working on new methods for estimating wasting incidence, prevalence and intervention coverage which can be adopted by development actors. For example, looking at trends in treatment program admission to understand whether wasting prevention interventions are effective.

- Build data literacy. The same indicators can be used in different ways to inform humanitarian vs. development priorities. Correct interpretation requires a combination of core nutrition and data-related knowledge and skills. For example, in emergency contexts Minimum Dietary Diversity (MDD) can increase if households start to forage for leafy vegetables. Nuanced interpretation requires that people understand how indicators are constructed and collected.

- Enhance data integration and government ownership. Establishing protocols for integrating partner data with government information systems including the DHIS-2 is important for both humanitarian and development data producers. This may require investing in the interoperability of DHIS2 and other digital tools to improve adaptability and real-time capabilities.

Several institutions and initiatives are working to bridge the humanitarian-development NIS divide. For example, under the USAID ELEVATE, humanitarian agency Action Against Hunger is expanding a converge monitoring collaboration to include DataDENT and other development stakeholders. DataDENT included the humanitarian sector in our multisector nutrition data assessments in Ethiopia and Nigeria and our ongoing work on data literacy. The EC-JRC is currently evaluating the impact of NIS within humanitarian and developmental frameworks in several countries, using MDD-W as a key indicator across contexts.

Together this work will contribute to a high-level event planned for June 2025 that will be co-organized by EC-JRC, NIPN, and partners with support of DataDENT to advance ideas around how to bridge humanitarian and development through a more unified nutrition data ecosystem and to gain commitments from international partners towards realizing it. Check this blog for updates after the meeting.