DataDENT has been tackling the challenge of designing indicators and survey questions about nutrition intervention coverage that are clearly understood by respondents while also providing the information that data users need. Cognitive interviewing is an essential step in our indicator and household survey question design work, including recent efforts for Nutrition-Sensitive Social Protection (NSSP) programs. Cognitive interviews are a qualitative method used to elicit insights into how questions and response options may cause cognitive error among respondents and into how to improve them (Willis & Miller, 2011).

Design challenge: NSSP coverage measurement

NSSP is a broad term for poverty-reduction programs that address underlying determinants of malnutrition. NSSP typically includes intervention components such as nutrition counseling or provision of fortified supplementary foods that are targeted to nutritionally vulnerable household members such as pregnant women or young children (Alderman 2016, Olney 2021, Manley 2020).

In a November 2023 blog, we highlighted several challenges to measuring NSSP program coverage using household surveys. First was clarifying the defining features of NSSP from a technical perspective. A second challenge was identifying whether respondents can reliably report on NSSP receipt. DataDENT faced similar challenges with measuring maternal micronutrient coverage and the distinction between iron-folic acid (IFA) and multiple micronutrient supplements (MMS).

In 2024, DataDENT partnered with Addis Continental Institute of Public Health (APHRC) in Ethiopia and with icddr,b in Bangladesh. The teams interviewed program staff in study areas to document key components of existing NSSP programs and interviewed community members to identify how they recognized and referred to these programs. The findings along with questions from previous surveys, informed our first draft of household survey questions and response options about: 1) whether respondents received a transfer (food/cash/in-kind); 2) who in the household the transfer was for; and 3) whether any other health or nutrition interventions received were linked to the transfer. Potentially linked interventions included nutrition and health counseling, referrals to health facilities, deworming tablets, micronutrient supplements, and/or fortified food transfers.

Cognitive testing method

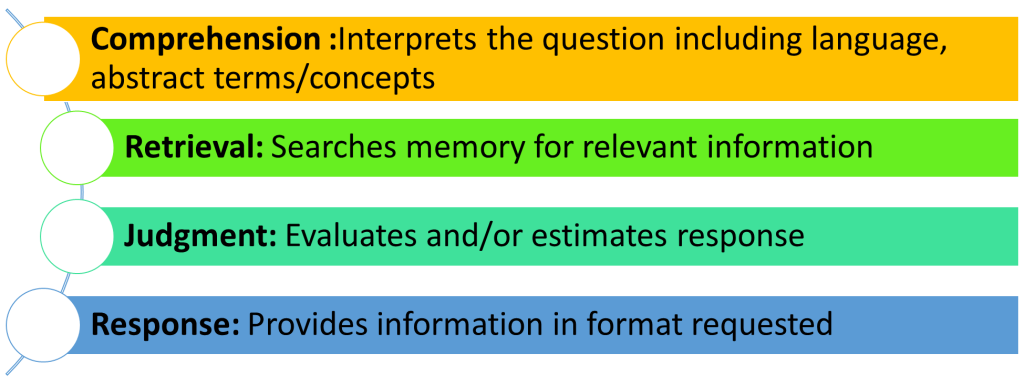

In each country, research teams carried out two rounds of cognitive interviews to refine the questions. We had some ideas about which parts of the questions might be problematic and developed open-ended, scripted probes to identify 4 types of “cognitive error,” i.e., differences between how researchers intended a question and how respondents understand it (Figure 1). In Ethiopia, we engaged 27 women and 15 household heads across rounds, and 25 women and 25 household heads in Bangladesh. We interviewed both women and the heads of their households because we wanted to identify who is most knowledgeable about NSSP programs and the program elements received. Below, we highlight key takeaways from our cognitive interview findings.

Image 1. The four cognitive stages

Takeaway #1: Researchers and respondents think about the same concepts differently (comprehension errors)

Comprehension errors were the most common error type across our draft questions and response items. Respondents had difficulty understanding certain response options (e.g. “fortified food” in both countries) and terms that had been used in other national surveys (e.g. “subsidized food” in Ethiopia).

There was also poor understanding of questions about receipt of other health or nutrition interventions “linked” to the food or cash transfer. The concept of ‘linkage’ proved too complex. Respondents could answer separately a) whether they received a transfer and b) whether they received a health or nutrition intervention with the transfer. However, when asked if and how they associated the transfer with those interventions, their answers varied widely.

Based on these findings, we shortened the questions and response options and used simpler words to improve clarity. Even after doing this, the survey question asking about “linked interventions” remained poorly understood and warrants further testing and refinement.

Takeaway #2: Who should answer questions about NSSP is not straightforward (retrieval error)

We observed discrepancies in responses between 32 out of 54 pairs of women and household heads (mostly male) who we interviewed about the types of food and cash transfers their household received. We did not find any consistent patterns in how the responses diverged by respondent type.

These discrepancies suggest that there may be retrieval errors and/or that different household members may possess partial/different knowledge about NSSP program benefits. To better understand these dynamics, we further tested differences by respondent type in the One Nutrition Coverage Survey (ONCS) in Bangladesh.

Image 2. A beneficiary of Agriculture, Nutrition, and Gender Linkages (ANGeL) project, Photo Credit: Julie Ghostlaw (IFPRI), Bangladesh

Takeaway #3: Understanding the cultural context aids interpretation of quantitative results (judgement error)

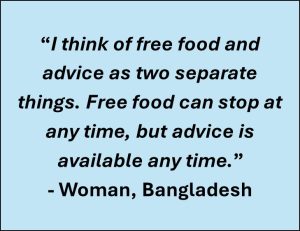

Household heads were asked whether someone in their household had received a “free or subsidized food” transfer (the draft survey question) and then asked to explain what receiving a food transfer meant in their own words (the related cognitive probe). Surprisingly, a few men in Ethiopia reacted negatively to the cognitive probe, showing evidence of judgement error. The men explained that responsible men do not need food transfers as they can provide for their families on their own; such a reaction likely stems from gender norms that expect men to be the primary breadwinners in Ethiopia. While this judgement error finding did not lead us to revise the survey item, it reveals potential social desirability bias in response to this survey question.

Takeaway #4: Fortifying weak points in survey items (response error)

Sometimes, respondents cannot answer a question using the format of the response options provided to them. When asked about frequency of receiving a particular NSSP transfer, some respondents did not understand the response option “a few days a week.” Accordingly, we updated the item to specify how many days are “a few” (i.e., 3 to 5 days) and recommend that enumerators be trained to recognize and record what counts as “few days.”

Image 3. Field team members conducting a vendor interview at a retail shop as part of the market landscaping survey. Photo Credit: Samuel Scott (IFPRI), Addis Ababa, Ethiopia

What is next?

Cognitive interviews were helpful in improving the content and face validity of the survey items. The final questions were implemented in the ONCS Survey in Bangladesh and analyzed for additional insights. The combined insights from cognitive testing and the questions used in the ONCS will be shared in forthcoming manuscripts and a toolkit of ONCS materials. For NSSP coverage measurement more broadly, further work is needed to identify the best coverage measures across contexts.

Follow DataDENT on social media to know when these and related outputs are available.