Maternal nutrition has been gaining traction as a policy priority across low-and middle-income countries (LMIC). Investing in good nutrition for women before and during pregnancy is fundamental for the health and survival of both mothers and infants. According to the WHO’s 2023 Born too Soon report, 1 in 4 infants globally – an estimated 35.3 million – were born either too soon (preterm), too small (SGA), or low birthweight.

To improve birth outcomes and other aspects of maternal and child health and wellbeing, WHO guidance on antenatal care for a positive pregnancy experience, released in 2016 and updated in 2020, recommends micronutrient interventions including, iron and folic acid (IFA), multiple micronutrient supplements (MMS), calcium as well as balanced energy protein (BEP) for general or context-specific delivery. National and global nutrition stakeholders – including policy makers, researchers, UN agencies, and advocates – have been working to operationalize these nutrition interventions within and across LMICs. Countries vary in MMS, calcium, and BEP implementation status, but most have a long history of providing IFA through antenatal care.

National, sub-national, and global actors need reliable data on who is being reached with maternal micronutrient interventions. In a 2020 study of nutrition data use, 75% of the 235 respondents representing 116 countries reported regularly accessing data on IFA consumption for decision-making. According to a 2019 report on Improving Antenatal Iron-Containing Supplementation Indicators by WHO-UNICEF’s Technical Expert Advisory Group for Nutrition Monitoring (TEAM), 58 respondents (out of 145 total respondents) representing 31 countries rely on household survey data to monitor IFA. Stakeholders value administrative data on IFA delivery collected through Health Management Information Systems (HMIS) but recognize data quality challenges. Many stakeholders also reported that the data they used was not available as frequently and/or as recently as they would like.

How do we currently measure receipt of maternal micronutrients in household surveys?

The Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) core questionnaire includes three questions about receipt and adherence to iron-containing supplements and are posed to mothers with live births in the last three years (Figure 1). To respond, mothers must recognize the translation of the term “iron tablets or iron syrup” used in that context and differentiate it from other pills, capsules, or syrups they acquired throughout pregnancy. They must also estimate their daily consumption over the course of a pregnancy that ended up to three years ago. People have long questioned the validity of this report.

| NO. | QUESTIONS AND FILTERS | CODING CATEGORIES | ||

| 426 (3) | During this pregnancy, were you given or did you buy any iron tablets or iron syrup? SHOW TABLETS/SYRUP/MULTIPLE MICRONUTRIENT SUPPLEMENT. |

YES | 1 | |

| NO | 2 | |||

| DON’T KNOW | 3 | |||

| 427 (1) (3) | Where did you get the iron tablets or syrup? Anywhere else? PROBE TO IDENTIFY THE TYPE OF SOURCE IF UNABLE TO DETERMINE IF PUBLIC, PRIVATE, OR NGO SECTOR, RECORD ‘X’ AND WRITE THE NAME OF THE PLACE(S). |

PUBLIC SECTOR | ||

| GOVERNMENT HOSPITAL | A | |||

| GOVERNMENT HEALTH CENTER | B | |||

| GOVERNMENT HEALTH POST | C | |||

| MOBILE CLINIC | D | |||

| COMMUNITY HEALTH WORKER/ FIELD WORKER |

E | |||

| OTHER PUBLIC SECTOR (SPECIFY) | F | |||

| PRIVATE MEDICAL SECTOR | ||||

| PRIVATE HOSPITAL | G | |||

| PRIVATE CLINIC | H | |||

| PHARMACY | I | |||

| PRIVATE DOCTOR | J | |||

| MOBILE CLINIC | K | |||

| COMMUNITY HEALTH WORKER/ FIELD WORKER |

L | |||

| OTHER PRIVATE MEDICAL SECTOR (SPECIFY) | M | |||

| NGO MEDICAL SECTOR | ||||

| NGO HOSPITAL | N | |||

| NGO CLINIC | O | |||

| OTHER NGO MEDICAL SECTOR (SPECIFY) | P | |||

| OTHER SOURCE | ||||

| SHOP | Q | |||

| MARKET | R | |||

| (MASS DISTRIBUTION CAMPAIGN) | S | |||

| OTHER (SPECIFY) | I | |||

| 428 (3) (4) | During the whole pregnancy, for how many days did you take the iron tablets or syrup? IF ANSWER IS NOT NUMERIC, PROBE FOR APPROXIMATE NUMBER OF DAYS. |

DAYS | ||

| DON’T KNOW | 998 | |||

Figure 1: Questions from DHS-8 core questionnaire about iron-containing supplements Are these household survey estimates of micronutrient coverage valid?

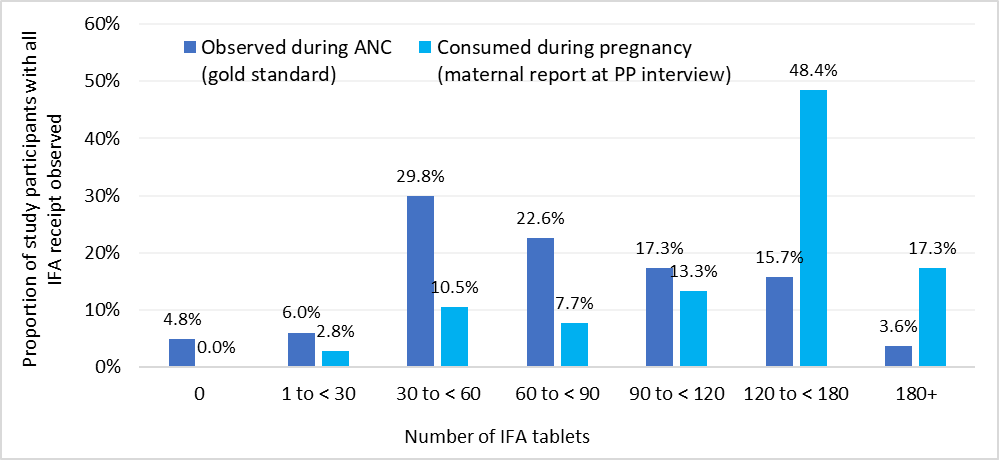

A recent validation study conducted by Johns Hopkins University in Nepal showed that at population-level women who are six months postpartum accurately reported whether they received any IFA during pregnancy. However the women over-reported the total number of IFA tablets they received (Figure 2), producing extremely biased population coverage estimates. DataDENT supported follow-up cognitive interviews with select women who said that they found the question about the number of tablets difficult and intimidating to answer. The validation study authors do not recommend using the questions they tested with post-partum women to assess the coverage of the amount of IFA received during pregnancy. They recommend additional research to identify a better measurement approach.

Figure 2. Distribution of observed IFA receipt versus reported days consumed among women in Nepal validation study with all IFA receipt observed (N=248)

How can we better measure adherence to micronutrients during pregnancy?

The DHS core questionnaire does not include questions specific to MMS, calcium, or BEP. MMS are iron-containing supplements, but it is not clear that they will be understood as “iron tablets”. Also, national and global stakeholders may want to track MMS scale-up relative to IFA, requiring questions that differentiate between them.

Questions to measure adherence to any daily micronutrient supplement will face similar challenges to those identified by the studies referenced above. However, MMS and calcium, which are generally delivered in a white tablet, may be more challenging to differentiate than IFA, which is a very distinct small red pill. Questions about coverage of BEP cannot be standardized until there is a clear and measurable definition of what qualifies as BEP.

To address these challenges, DataDENT is collaborating with research partners in India and Ethiopia to generate evidence around new approaches for measuring prenatal IFA, MMS and calcium coverage in national household surveys. We aim to develop new survey questions and accompanying recall aids that account for how women themselves differentiate micronutrient supplements from other products used during pregnancy and how they understand and report adherence. We will also explore new sampling approaches that include both postpartum and currently pregnant women.

We expect to complete this development work in mid-2024 and will share guidance to support uptake of the questions in national nutrition surveys and other data collection opportunities.