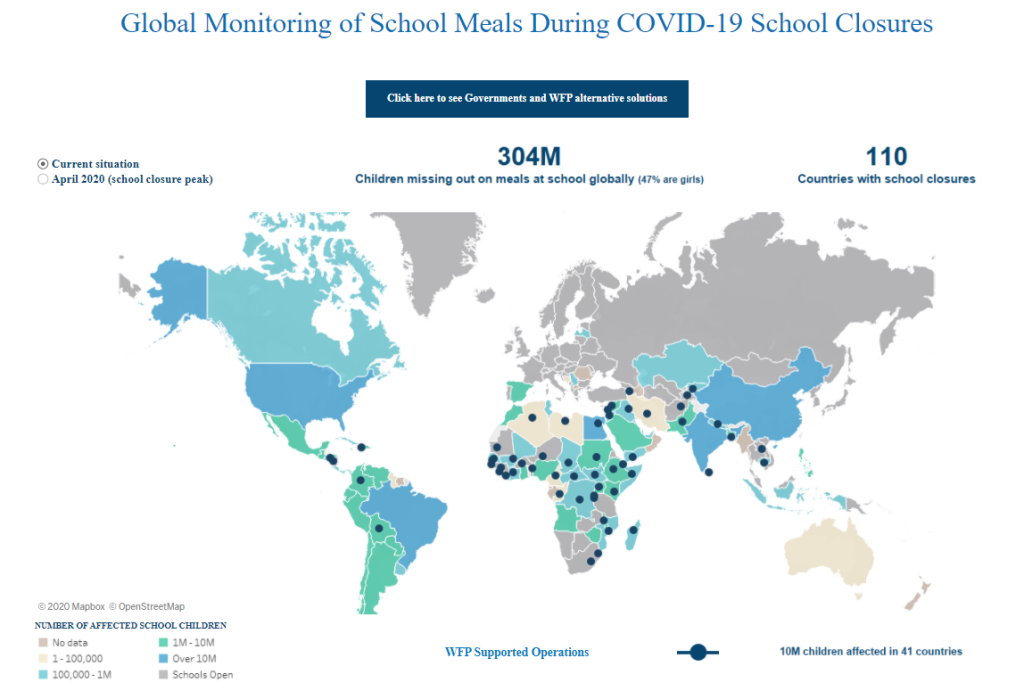

Schools across the world closed alongside national lockdowns to contain the spread of COVID-19, leaving many children without access to school meals. Schools are important platforms for delivering high-impact health, nutrition-specific, and nutrition-sensitive interventions like school feeding programs. The World Food Programme (WFP) launched the Global Monitoring of School Meals during COVID-19 School Closures map in March 2020 to track the number of children missing school meals and “alternative solutions” undertaken by governments and WFP to reach these children during the pandemic.

Today, the WFP reports that 304 million children are still missing out on school meals, highlighting how school feeding programs must evolve for children facing food insecurity. Carmen Burbano, director of WFP’s school meals division, discussed how WFP is adapting its programs globally in interviews with [Devex] and [the New Humanitarian]. Common alternative interventions are take-home rations and cash-based transfers; some countries use a mix of interventions. India’s approach incorporates cash-based transfers to households, distribution of uncooked grains and cooked meals, and school meal delivery. Level of implementation of these programs may be mixed [Scroll.in]. In Latin America and the Caribbean, governments and experts shared efforts in the regional symposium “Ensuring safe school feeding during and after the pandemic: an emerging agenda” hosted in September [The Caribbean Globe].

There have always been widespread gaps in data on the coverage of nutrition-sensitive social protection programs such as school feeding programs, take-home rations, and cash-based transfers. As these programs are scaled up to respond to food insecurity exacerbated by COVID-19, these programs must be measured to improve our understanding of impact.