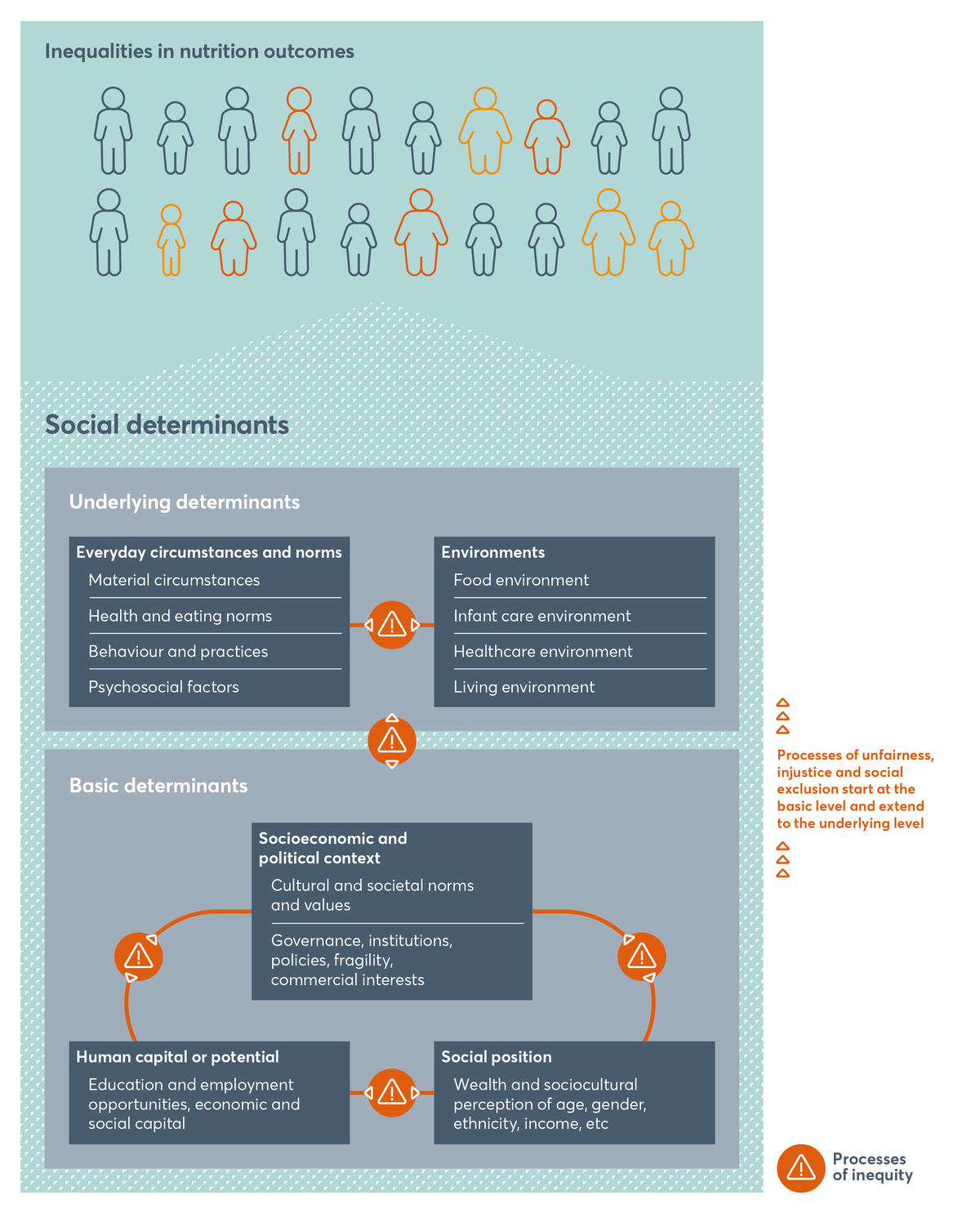

Gender is a social determinant of health which can have a significant impact on an individual’s nutrition status. The 2020 Global Nutrition Report (GNR) Nutrition Equity Framework illustrates how basic and underlying determinants, including gender, are interlinked and contribute towards nutrition inequity. Sociocultural perception of gender affects power dynamics and access to nutrition services and interventions. For example, gendered norms can influence who in the household makes decisions related to food purchasing and allocation and agricultural production. Promoting gender equity in nutrition is recognized as a critical gap to fill to achieving Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 2—Ending Hunger in All its Forms—and is a theme for the Tokyo Nutrition for Growth Summit 2021.

Household surveys are the primary source of sex-disaggregated nutrition data. However, household-level data can be insufficient at documenting gender-related inequities in food security within a household. To better understand why it is important to consider gender when measuring and addressing food insecurity, I spoke with Dr. Nzinga Broussard, Senior Director of the Global Innovation Fund, to discuss her paper “What explains gender differences in food insecurity?”.

Figure 1: Nutrition equity framework (Global Nutrition Report, 2020)

Q: In August 2020, CARE released a report that described the lack of data on how COVID-19 has affected food security among women compared to men. This food insecurity gender data gap existed prior to the pandemic. Why do we know so little about how food security disproportionately affects women? Why is it important to consider gender when measuring and addressing food insecurity?

The reason we know so little about how food insecurity disproportionately affects women is because of the way most food insecurity measures are constructed and analyzed. Most food insecurity questions are asked at the household level, which requires inferences about the gendered aspect of food insecurity. The few measures that are asked at the individual level, with the exception of the Food Insecurity Experience Scale (FIES), can be costly (both in terms of financial and time cost) to collect, resulting in inconsistency in how these measures are collected across geography and time. This results in an inability to fully understand patterns of food insecurity of women relative to men.

It is important to consider gender when measuring and addressing food insecurity because women play an important role in their households and in the economy. When women have more resources and are more food secure, their households and communities are more food secure. Additionally, women are productive members in the economy. If they are disproportionately more likely to be food insecure, there may be important productivity implications.

Q: What do you consider the key takeaways in your analysis? Was there anything that you were surprised by?

The key takeaways from my paper were 1.) that a gender gap in food insecurity exists in most countries, regardless of the level of development of the country; 2.) most of the gender gap in food insecurity can be explained by gender differences in educational attainment, employment status, and social networks. By addressing the gender differences in educational attainment and employment status (areas that can be addressed by appropriate policies), we can address the gender gap in food insecurity.

The most surprising observation from my analysis was that a country’s level of development did not make it immune to gender differences in food insecurity.

Q: You conducted your analysis using the FIES. Since your analysis, use of FIES has expanded as it has been a key tool in measuring food insecurity during COVID-19 and has been added as an optional module to the Demographic and Health Survey. Why did you choose the FIES scale for your analysis and what were its limitations?

It is great to see the FIES adopted by more agencies and used in more surveys. At the time of my analysis, there was a lot of discussion about gender differences in food insecurity, but there was not a consistent measure of food insecurity across contexts. In some contexts, gender differences in food insecurity was observed from anthropometric data, in some contexts gender differences were observed from food consumption data, and in others they were observed from household experiential scales. To some degree, when talking about gender differences in food insecurity, it was always context or measure specific. The beauty of the FIES, and its inclusion in the Gallup World Poll, was that it was a single food insecurity metric that was consistent in over 150 countries.

Q: Why was a modification of the Blinder-Oaxaca decomposition required to execute this analysis? How did you handle unmeasured variables (i.e. those that are critical to food insecurity but did not have data available for analysis) in interpretation of your findings?

The Blinder-Oaxaca (BO) decomposition is primarily used in wage regressions, where the outcome variable, wages, is a continuous variable. Because the food insecurity measure I used was a binary variable (yes/no to being food insecure), I had to use the modified BO decomposition that takes into consideration a binary variable. But the interpretation of the decomposition is the same as what the interpretation would be if the variable of interest were a continuous variable.

A nice feature of the BO decomposition is that it allows us to see how much of the gender gap is explained by the observed variables. Ultimately, the analysis was asking how much of the gender gap in food insecurity would still exist if we addressed the gender gap in the observed variables (i.e. education, employment, social networks, etc.). What I show is that, in many countries, most of the gender gap in food insecurity can be explained by gender differences in educational attainment, employment, and social networks. If we removed the gender gap in these outcomes, we would remove the gender gap in food insecurity.

In the field of labor economics, the BO decomposition has been used to explain racial and gender differences in wages. Labor economists go a step further than just investigating the racial/gender gap that can be explained by the racial/gender gap in observed characteristics (e.g., educational attainment), but also account for how much of the racial/gender gap can be explained by discrimination in the labor market. This is captured by the share of the racial/gender gap that is not explained by observed characteristics (i.e., the unexplained/unmeasured share). I chose not to focus on the unmeasured source of the gender gap because there were some variables that I was unable to include in the analysis as the information was not collected in the GWP. It was impossible for me to distinguish between discrimination as an explanation for the remaining gender gap in food insecurity versus variables that were not included in the analysis. The analysis controlled for country specific factors that might contribute to a gender gap in food insecurity, for example cultural norms that are country specific. But individual unmeasured variables were captured by the unmeasured source of the gender gap. For example, access to transportation was not used in the analysis because an acceptable measure of access to transportation was not measured in the GWP. However, access to transportation decreases the likelihood that an individual would be food insecure. It is also more likely that men have better access to transportation than women. The exclusion of access to transportation in the analysis does not change the results on what I found on employment, education, and social networks. But it would have limited what I could have said about whether the remaining gender gap in food insecurity was explained by gender discrimination in access to food resources.

Q: What is the role of culture and related household dietary practices in the food insecurity gender gap? Was this considered in the decomposition analysis?

Due to data limitations, I was unable to investigate the role of culture or related household dietary practices. However, my analysis shows that between 25 and 95 percent of the gender gap in food insecurity is explained by the observed variables included in the analysis. For the countries/regions where the majority of the gender gap is explained by gender differences in education, employment, and social networks, it is safe to say that culture and household dietary practices are not the primary reasons for the gender gap. However, for the countries/regions for which a large share of the gender gap in food insecurity cannot be explained by gender differences in education, employment, and social networks then additional analysis would be necessary to better understand the role of culture and household dietary practices.

Q: How can these findings be translated into programs and policy to address gender inequality in food security?

The paper argues that policies that address gender differences in educational attainment and employment can have long run implications for food insecurity. While it is important to directly address the gender gap in food insecurity, for example, by targeting women and girls directly for food aid programs, policies that address the root causes of the gender gap in food insecurity can be equally or more impactful. For example, a negative shock to a community may require community members to find additional temporary employment, however if there are barriers that prevent women from having equal access to temporary employment, then it is likely that the negative shock will disproportionately impact women who do not have the same access to temporary employment as a mitigating factor to the negative shock.

Q: How can we more accurately capture differences in food security among men and women? What are promising examples that you have seen partners undertake to tackle the food insecurity gender data gap?

The best way to accurately capture differences in food security among men and women is to collect individual level information on food security status. But it needs to be done consistently and regularly. The use of a measure like the FIES in nationally representative household surveys that are administered frequently (e.g., every 5 years, annually like what is done in the US, or biannually to capture peak and lean seasons for countries with a large share of the population working in agriculture), would allow us to better understand the factors that contribute to food insecurity and the gender gap in food insecurity, as well allow us to track how food insecurity and the gender gap in food insecurity is changing overtime.